The Facts: Priesthood and Race in LDS History

Introduction

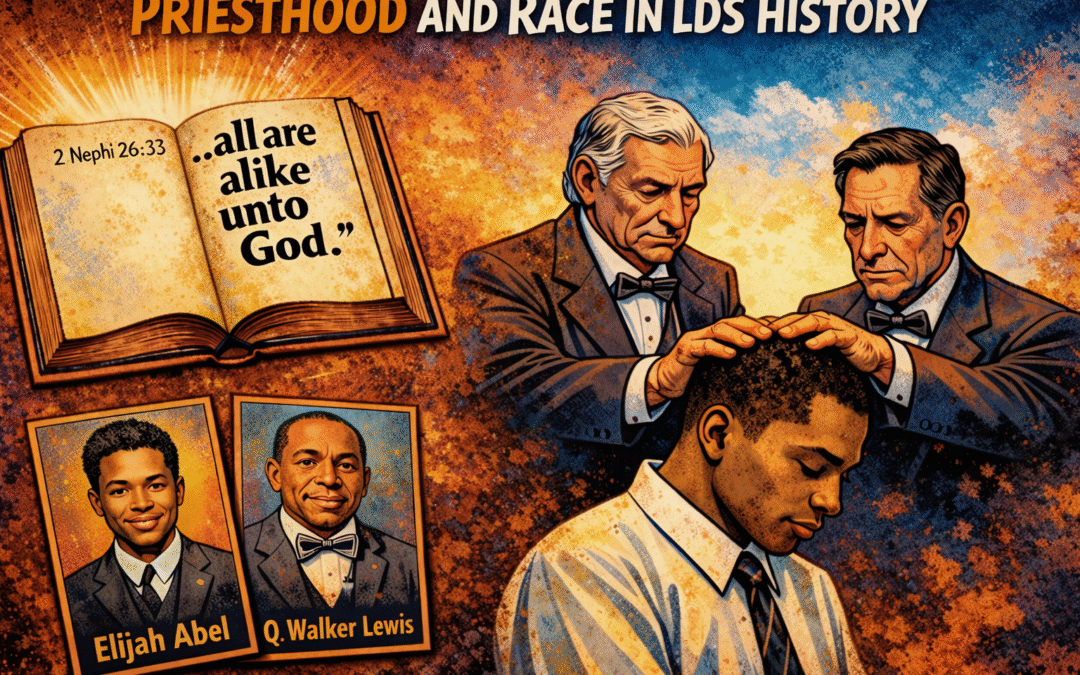

Joseph Smith’s Era: A Foundation of Inclusion

Joseph Smith, the founding prophet of the LDS Church (1830–1844), did not institute a race-based priesthood ban. On the contrary, during Joseph’s lifetime a number of Black individuals became members of the Church and a few Black men were ordained to the priesthood churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. For example, Elijah Abel (sometimes spelled Able) was a Black Latter-day Saint ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood in 1836; he participated in temple ceremonies in Kirtland, Ohio, and later performed proxy baptisms for deceased relatives in Nauvoo churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Another Black member, Q. Walker Lewis of Massachusetts, was also an ordained elder. There is no reliable evidence that any Black man was ever denied the priesthood under Joseph Smith’s leadership churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. In fact, toward the end of his life Joseph Smith openly opposed slavery, aligning with abolitionist sentiments churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. He welcomed people of all races into the Church by allowing baptism for anyone willing to accept the gospel, and the early Church had no policy of segregated congregations churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Contemporary historians affirm that the priesthood ban “did not exist” during Joseph Smith’s tenure archive.sltrib.com. Joseph even personally associated with and ordained at least a few African Americans, reflecting his stance that God “denieth none” who come unto Him archive.sltrib.com churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

It is important to note the broader context of race in early 19th-century America. The Church was established in 1830 in a nation where slavery was still legal in the South, and racist attitudes were common virtually everywhere among white Americans churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Many contemporary Christian churches were segregated by race churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Joseph Smith’s relative inclusivity was remarkable for his time. He advocated for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people and espoused equality in a period when the U.S. Supreme Court would later infamously declare that Black people had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect” (Dred Scott, 1857) churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This is not to say early Latter-day Saints were completely free of the racial prejudices of their day, but Joseph’s actions set a precedent that, initially, church membership and even priesthood ordination were open to all worthy men, regardless of race churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

The Origin of the Priesthood Ban under Brigham Young

After Joseph Smith’s death in 1844, the Church’s leadership fell to Brigham Young, who led the Latter-day Saints’ migration to Utah. In 1852, Brigham Young publicly announced a new policy: men of Black African descent were no longer to be ordained to the LDS priesthood churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This marked the clear beginning of the priesthood restriction. That same year, Brigham Young—who was by then both Church President and territorial governor—addressed the Utah territorial legislature. He declared the policy of priesthood denial for Black males even as the territory passed laws permitting a form of Black “servitude” churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. It appears Brigham Young was influenced by widespread racial ideas of his era, including the belief that Africans were under the biblical “curse” of Cain and/or Ham, which supposedly marked them with dark skin churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Brigham echoed these justifications when instituting the ban, ascribing it in part to God’s curse on Cain and the lineage of Cain through Ham’s son Canaan churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Such notions were commonplace in 19th-century America and used by many to rationalize slavery and segregation churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. In Brigham’s worldview (shared by many contemporaries), persons of African descent were seen as a cursed lineage who would have to wait for certain blessings.

Despite implementing this restriction, Brigham Young also prophesied that it would not be permanent. In the same speeches where he announced the ban, he stated that at a future date Black Church members would “have all the privilege and more” enjoyed by other members churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. In other words, Brigham believed Black Saints would eventually receive every blessing, including priesthood and temple rites, at some future time determined by the Lord. This forward-looking caveat is significant: it indicates that even as the ban began, there was an expectation (at least by Brigham Young and subsequent leaders) that God’s “long-promised day” for full inclusion would one day come churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Indeed, later Church presidents like Heber J. Grant and David O. McKay privately affirmed their view that the restriction was temporary and would be lifted by revelation at the proper time en.wikipedia.org[2].

Why did Brigham Young initiate the ban? The exact rationale was never canonized as doctrine, and no revelatory document from that time exists mandating it. Rather, Brigham appears to have acted in line with the racial attitudes and pressures of the 1850s. Some background: the Utah Territory in 1852 was grappling with the question of slavery because a number of Latter-day Saint converts from the American South had brought enslaved people to Utah churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Brigham Young and the Utah legislature legalized a form of indentured servitude (believing it more humane than outright slavery) even as Brigham announced the priesthood ban churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. The ban may have been an effort to reconcile pro-slavery settlers or to prevent sociopolitical conflict, reflecting a desire to appease pro-slavery attitudes while distinguishing Utah from the slaveholding South. In any case, church records and historical analysis make clear that the ban was implemented under Brigham Young’s leadership—not Joseph Smith’sarchive.sltrib.comarchive.sltrib.com. Modern LDS scholars and the Church itself acknowledge that Brigham Young was influenced by “common beliefs of the time” regarding racial inferiority, and thus the origin of the ban was more rooted in 19th-century racism than in divine revelation archive.sltrib.com archive.sltrib.com.

Life Under the Priesthood Ban: Policies and Theories (1852–1978)

For over a century after 1852, the LDS Church continued to teach the gospel to people of all races (anyone could be baptized a member), but Black members of African descent faced specific restrictions. Black men could be baptized and receive the gift of the Holy Ghost, but they were not permitted to be ordained to any office in the lay priesthood (which in the LDS Church is normally conferred on virtually all worthy male members) churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. In addition, Black men and women of African descent were not allowed to participate in temple ordinances such as the endowment or eternal marriage sealings churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. These temple rites are considered essential LDS sacraments for the fullest blessings of salvation. Thus, the ban had profound spiritual and practical implications: faithful Black Latter-day Saints could not hold church leadership positions requiring priesthood, and Black families could not be sealed in LDS temples for eternity during that era.

Throughout this period, many devoted Black Latter-day Saints still found ways to contribute and remain loyal to their faith. Notably, a few Black men who had been ordained before the ban continued to hold their priesthood. Elijah Abel himself remained a member in good standing and even served several missions; however, when he requested permission in 1879 to receive his temple endowment, that request was denied due to the racial policy churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Another early Black member, Jane Manning James, who had been a close friend and servant in Joseph Smith’s household and later crossed the plains to Utah, repeatedly petitioned to enter the temple. She was only allowed limited access (performing baptisms for the dead on behalf of her ancestors) but was barred from other ordinances like the endowment during her lifetime churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. These examples underscore the painful reality of the ban for Black Latter-day Saints, who exhibited tremendous faith and patience despite being restricted from the full blessings available to others.

During the decades of the ban, numerous theories circulated among Church members and leaders to explain or justify it. It’s crucial to understand that none of these explanations were ever canonized as official doctrine, and the Church today explicitly disavows them churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. But historically, they influenced LDS folklore and attitudes. Among the prominent theories were:

Curse of Cain/Ham: The notion that Black Africans carried the “mark of Cain” for Cain’s ancient sin of murdering Abel, as well as the idea that Noah’s grandson Canaan (son of Ham) was cursed with servitude and blackness churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This theory supposed that this divine curse made Black people ineligible for priesthood until God removed the curse. Variations of this claim were commonly taught or assumed in early Mormonism and mirrored Protestant American beliefs about Africans’ destiny churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Less Valiant in Premortal Life: By the early 20th century, another idea gained currency—that Black people had been “less valiant” in the premortal existence, meaning that in the pre-earth life (when spirits ostensibly chose sides in a war in heaven) Black souls did not fight as fervently for God’s plan and thus were born into lineages banned from priesthood as a consequence churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This was a speculative attempt to fit the ban into LDS theology of a premortal life.

Interracial Marriage and Racial Purity: Some leaders taught that God forbade interracial marriages (miscegenation) and that maintaining the ban helped prevent such unions, or that mixing lineages was against divine law. For instance, well into the 20th century, church leaders like Elder Mark E. Petersen argued against interracial dating, reflecting broader societal taboos of the time.

Patriarchal Lineage Explanations: In LDS belief, priesthood was seen as following lineage of certain biblical tribes. Some suggested Black Africans were not eligible because they weren’t of the line of Israel or had a separate lineage (though this was inconsistent with other non-Israelite groups receiving priesthood).

These theories were often presented as possible reasons for God’s will, but they were not revealed truths. Significantly, LDS prophets from the mid-20th century onward questioned these folk doctrines and over time repudiated them. Today the Church has forcefully stated that black skin is not a divine curse, there was no premortal misdeed by Black souls, interracial marriage is not a sin, and no race is inferior to another churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. All past justifications for the ban are disavowed as the products of racism and speculation, not of revealed doctrine archive.sltrib.com churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Through the years of the ban, church leaders themselves were sometimes uncertain and divided about its origin and status. Importantly, many early Latter-day Saints (especially after Brigham Young’s time) mistakenly assumed the ban had originated with Joseph Smith and thus must have been God’s will from the start en.wikipedia.org[2]. This widespread assumption made it difficult to reconsider the policy—after all, if a prophet (Joseph) had established it by command of God, who were they to reverse it without an equally clear divine mandate? However, by the 1960s-1970s, scholarly research (notably by LDS scholar Lester E. Bush in 1973) demonstrated that no evidence of a priesthood ban existed before 1852, strongly suggesting that Joseph Smith did not originate it en.wikipedia.org[2]. This historical finding “made it easier” for Church leaders to contemplate change en.wikipedia.org[2]—essentially realizing that the ban was a policy implemented under specific historical conditions, rather than an eternal, unchangeable doctrine.

Growing Pressures and Steps Toward Change in the 20th Century

By the mid-20th century, societal attitudes on race were shifting and the LDS Church found itself increasingly at odds with the emerging ethos of racial equality. The Civil Rights Movement brought intense scrutiny. External pressures mounted: the NAACP and other civil rights groups in the 1960s publicly protested the Church’s racial policy. In 1963, to preempt a planned NAACP protest at LDS General Conference, an LDS apostle (Hugh B. Brown) issued a statement supporting civil rights and human dignity en.wikipedia.org[2]. Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were high-profile boycotts and demonstrations—for example, Black athletes at various universities refused to compete against teams from BYU due to the Church’s discrimination en.wikipedia.org[2]. In 1974, protests arose over the Church’s policy disallowing Black Boy Scouts from serving in LDS scout troops as leaders en.wikipedia.org[2]. The Church’s growth also meant more global attention, and its stance on race became a missionary obstacle and a public relations challenge.

Internal challenges were also significant. The Church was expanding into areas like Brazil, the South Pacific, and eventually Africa—regions with racially mixed populations or Black majorities. This posed practical problems: How could one determine who had “African” ancestry sufficient to be barred? In places like Brazil where interracial mixing was extensive, implementing the ban consistently was nearly impossible en.wikipedia.org[2]. For years, in South Africa, the Church had required priesthood candidates to trace their genealogy to ensure no Black African lineage churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. President David O. McKay (Church president 1951–1970) found this unworkable: in 1954, while visiting South Africa, he changed the policy to presume a person was eligible unless known otherwise (essentially reversing the burden of proof) churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. He also clarified that the ban applied only to those of Black African descent—other dark-skinned peoples (e.g., Polynesians, Fijians, Australian Aboriginals) were never barred from priesthood churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Under McKay, the Church even began missionary work in Fiji and elsewhere among non-African dark-skinned peoples, underscoring that the restriction was tied specifically to African lineage churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

President McKay is a pivotal figure because he wrestled with the ban on principle. He stated that it was a “policy” not doctrine (though in LDS practice the line between those can blur), and he sincerely sought divine guidance on whether it could be lifted churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. McKay prayed repeatedly for a revelation to end the restriction but reported that he “did not feel impressed” to lift it at that time churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Essentially, McKay felt he could not change it without an unmistakable revelatory mandate. Other apostles concurred that only a clear revelation could alter such a long-standing policy. In 1969, the LDS apostles actually took a vote on rescinding the ban (reflecting a growing sense that change was needed), and a majority favored doing so—but one senior apostle, Harold B. Lee, objected that procedurally, it required a revelation. Lee’s position prevailed and no action was taken; he later became Church president himself (1972–73) and did not lift the ba nen.wikipedia.org[2].

Meanwhile, the Church’s worldwide mission to “teach all nations” (Matthew 28:19) felt increasingly incompatible with a policy that excluded certain races from full fellowship churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Key developments in the 1970s underscored this: in Brazil, the Church had flourished among people of mixed ancestry—so much so that a temple was announced for São Paulo in 1975. As construction progressed, church leaders encountered faithful Brazilian members (some with African lineage unknown or known) who had sacrificed to build the temple but would not be allowed to enter it once completed under the existing rules churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This moral contradiction weighed heavily. Additionally, in West Africa (Nigeria and Ghana), thousands of sincere individuals had discovered Mormonism and were living its teachings, waiting for the Church to formally establish itself there churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. The Church hesitated to organize fully in those nations because of the ban—how could they preach a gospel of Christ to these nations yet tell converts they could not receive priesthood or temple blessings? By the mid-1970s, it became clear that the growth and global mandate of the Church were being hampered by the ban churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Church leaders like Spencer W. Kimball (who became Church president in 1973) felt increasing spiritual urgency to resolve the issue.

In summary, three major forces converged by the 1970s:

Social Pressure and Moral Scrutiny: The civil rights era made the Church’s exclusion of Blacks a moral outlier; protests and public criticism brought unwanted attention.

Practical Administrative Difficulties: As the Church globalized (Brazil, Africa, the Caribbean, etc.), determining who was “Black African” became untenable and the ban impeded missionary work.

Prophetic Re-evaluation: Top LDS leaders prayerfully reconsidered the scriptural and historical basis (or lack thereof) for the ban. Research showing Joseph Smith’s lack of involvement helped them see it as changeable. Leaders like Spencer W. Kimball were deeply sympathetic to the plight of Black members and were motivated by a conviction that the gospel should be for “every nation, kindred, tongue, and people” without restriction churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

The 1978 Revelation and Official Declaration 2

By early 1978, Spencer W. Kimball—who had long been a compassionate advocate for all people—was intensely focused on seeking the Lord’s will regarding the priesthood ban. He spent many hours in private prayer and temple meditation on the subject en.wikipedia.org[2] en.wikipedia.org[2]. President Kimball even requested studies from apostles on the scriptural basis (or lack thereof) of the ban; notably, Elder Bruce R. McConkie produced a memo acknowledging no clear scriptural impediment to change en.wikipedia.org[2]. In Kimball’s heart grew a firm assurance that “the time had come” for the promised day of inclusion en.wikipedia.org[2].

On June 1, 1978, President Kimball convened a special meeting in the Salt Lake Temple with his counselors and available members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles en.wikipedia.org[2]. He shared with them his feelings, the spiritual promptings he’d received, and proposed that they unite in prayer to seek a divine confirmation. One by one, each apostle expressed support for lifting the ban—a remarkable consensus that had built up through the preceding months en.wikipedia.org[2]. They then joined together in a sacred prayer circle with President Kimball as voice, pleading for heavenly direction en.wikipedia.org[2]. What happened next is something those present described in awe for the rest of their lives: God answered with a powerful spiritual manifestation. Multiple apostles testified of feeling the Holy Spirit pour over them, giving unmistakable confirmation that the ban should be lifted en.wikipedia.org[2] en.wikipedia.org[2]. Elder McConkie said “the Holy Ghost descended upon us and we knew that God had manifested his will”—an experience beyond any he’d had before en.wikipedia.org[2]. Elder L. Tom Perry likened it to a “rushing of wind” that filled the room, leaving President Kimball visibly relieved and overjoyed en.wikipedia.org[2]. Elder Gordon B. Hinckley (who would later become Church President) described it as if “a conduit opened between the heavenly throne and the kneeling, pleading prophet”—an utterly sacred moment churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. There was no doubt among them that the Lord had spoken and given His approval to end the restriction newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3] newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3].

A week later, on June 8, 1978, the First Presidency (Kimball and his counselors) released an official letter to the Church announcing that “he (the Lord) has heard our prayers, and by revelation has confirmed that the long-promised day has come”—henceforth, “all of our brethren who are worthy may receive the priesthood,” regardless of race churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This landmark document, now known as Official Declaration 2, also made clear that all worthy members could receive temple blessings as well churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. The announcement was greeted with overwhelming joy and relief among Latter-day Saints around the world churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Many members (of all races) wept and rejoiced, feeling a heavy burden of uncertainty and division being lifted churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. The news made headlines nationwide, appearing on front pages and network news broadcasts en.wikipedia.org[2]. In the LDS communities of Utah and beyond, telephone lines were jammed with excited callers sharing the glad tidings en.wikipedia.org[2].

In October 1978, the Church’s general conference unanimously ratified the revelation, and Official Declaration 2 was added to the Doctrine and Covenants (one of the LDS canonized scriptures) en.wikipedia.org[2] en.wikipedia.org[2]. Although the text of the revelation itself (the spiritual experience in the temple) was not released, the official declaration presented it as the will of the Lord. It states that Jesus Christ, by revelation, confirmed that the time had come for every faithful, worthy man to receive the priesthood en.wikipedia.org[2]. Since then, Latter-day Saints commonly refer to this event as “the revelation on the priesthood.”

The aftermath of the 1978 revelation was immediate integration and further growth. Black men in the Church were ordained to the priesthood within days of the announcement; Black Latter-day Saints entered temples around the world soon after churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. The Church moved forward to establish units in West Africa, where large numbers of people were ready to join. In 1978, one of the first Black converts in the U.S., Brother Joseph Freeman, was ordained and later became the first Black man to officiate in an LDS temple. Over time, barriers in missionary work fell away—missionaries no longer had to screen for African ancestry or avoid teaching people of certain races en.wikipedia.org[2]. The Church could truly preach the gospel “to every creature,” consistent with its teachings that God is no respecter of persons.

Crucially, LDS leaders also recognized that previous statements about race now needed correction. In a remarkable show of humility, Elder Bruce R. McConkie—who before 1978 had himself taught some of the now-discarded theories—told members that new revelation had supplanted all old assumptions. “Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or… anyone else has said… that is contrary to the present revelation,” McConkie urged. “We spoke with a limited understanding… We have now had added a new flood of intelligence and light on this subject, and it erases all the darkness and all the views of the past” en.wikipedia.org[2]. In other words, prior teachings or conjectures about Black people and the priesthood “don’t matter anymore” in the light of God’s revealed will en.wikipedia.org[2]. This was a clear directive to let go of racist folklore and embrace the unity of God’s family.

The 1978 revelation is often likened by Latter-day Saints to the New Testament story of Peter’s revelation to take the gospel to the Gentiles (Acts 10)—a divine course-correction opening blessings to a group previously excluded. Church President Gordon B. Hinckley later testified that the 1978 event was undoubtedly “the mind and the will of the Lord”, recalling that sacred moment in the temple with reverence newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3] newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3].

Modern LDS Teachings on Race and Equality

In the decades since 1978, the LDS Church has worked to eliminate racism and make full inclusion a reality within its culture. The official stance today is one of total equality of races before God. In 2013, the Church published a comprehensive essay, “Race and the Priesthood,” which candidly acknowledged the ban’s history and disavowed previous justifications as rooted in racism rather than revelation archive.sltrib.com archive.sltrib.com. The Church affirmed that it “condemns all racism, past and present, in any form” archive.sltrib.com. It also clarified that the Church has no doctrine of curse or inferiority associated with skin color, and taught that God does not judge or favor His children on the basis of race churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This essay effectively “drained the ban of revelatory significance,” portraying it as a product of its time that eventually had to be corrected archive.sltrib.com. Scholars observed that this frank approach represented a maturation for the Church, aligning its narrative with historical truth and Gospel principles archive.sltrib.com.

Church leaders have repeatedly echoed these sentiments. For instance, in a notable sermon in 2006, President Gordon B. Hinckley deplored any lingering racial prejudice, declaring: “No man who makes disparaging remarks concerning those of another race can consider himself a true disciple of Christ. … There is no basis for racial hatred among the priesthood of this Church.” newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3] newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3]. He reminded the congregation that the 1978 revelation was rejoiced in, and that the gospel leaves no room for racism. More recently, Church President Russell M. Nelson (the current prophet) has actively reached out to leaders of the Black community and spoken of building bridges of respect and charity. In 2020, amid racial turmoil in the United States, President Nelson stated on social media: “We abhor racism… any sense of superiority of one race over another. Today I call upon our members everywhere to lead out in abandoning attitudes and actions of prejudice.” Such statements reinforce that anti-racism is now the expectation within the Church.

The membership of the Church today reflects increasing diversity. Since 1978, hundreds of thousands of individuals of African descent have joined the LDS Church churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. Thriving congregations exist in Africa, the Caribbean, Brazil, and throughout the world, led by local priesthood holders of all races. In 2019, Elder Peter M. Johnson became the first African-American General Authority (a senior leadership position) and many Black Latter-day Saints serve in prominent roles. In Africa, where the Church has grown rapidly, multiple temples now dot the continent—a visible symbol that all blessings of the faith are available to everyone.

Most importantly, LDS theology emphasizes that through Jesus Christ, all humanity can be “one”. The Book of Mormon verse often quoted states that the Lord “denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free… all are alike unto God” (2 Nephi 26:33) churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. The New Testament similarly teaches that God is “no respecter of persons” (Acts 10:34) churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. These scriptural foundations underpin the modern Church’s stance: the true value of a soul has nothing to do with race. Any attitudes or practices that suggest otherwise are contrary to the Gospel of Christ.

Addressing Criticisms and Misconceptions

Criticism 1: “Joseph Smith or God instituted the ban, so the Church was following God’s will in being racist.”

Fact Check: This claim is not supported by historical evidence. As shown above, Joseph Smith did not start a priesthood ban—he ordained Black men and preached against slavery churchofjesuschrist.org[1] archive.sltrib.com. The ban began under Brigham Young in 1852, influenced by worldly racismarchive.sltrib.com. The Church today acknowledges the ban’s origins lay in cultural biases of that era, not an explicit commandment from Godarchive.sltrib.com. For faithful Latter-day Saints, this means the restriction was a policy allowed by God for a time, rather than a revealed eternal doctrine. In LDS belief, God sometimes allows His children (and even His Church leaders) to operate within the limitations of their environment until a greater light and knowledge is received (comparable to how ancient Israel operated under the law of Moses until Christ introduced a higher law). The 1978 revelation is understood as the moment when God definitively made His will known that all should be included—a course correction akin to Peter’s revelation to take the gospel to the Gentiles. Rather than seeing the ban as divine will, the Church sees the ending of the ban as divine will. President Kimball and the apostles specifically sought a revelation because they did not assume the policy was sacrosanct; they wanted God’s clear direction churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Criticism 2: “The LDS Church was just flat-out racist and only abandoned the ban due to public pressure or threats (not true revelation).”

Fact Check: There is no question that racist assumptions influenced many past Church leaders—the Church readily admits this and condemns past racism archive.sltrib.com churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. However, the claim that external pressure alone caused the 1978 change oversimplifies what happened. In truth, decades of external pressure (1930s–1970s) did not by themselves move the Church to act. The Church had endured criticism and even costs (e.g., public boycotts) for years, yet leaders remained firm that only a divine revelation could legitimately end the policy en.wikipedia.org[2]. In fact, the ban was lifted after the height of civil rights activism, not during its peak—by 1978, social pressure had somewhat subsided compared to the 1960s. What truly catalyzed the change was a combination of practical church growth needs and, fundamentally, spiritual seeking by the prophet. President Spencer W. Kimball was deeply troubled by the dissonance between the Church’s universal message and the exclusion of Blacks churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. He wore out his knees in prayer about it. The historical record (including diaries and statements from those present) affirms that Kimball and the apostles experienced a profound revelatory event on June 1, 1978 en.wikipedia.org[2] en.wikipedia.org[2]. LDS leaders consistently testify that this change came by divine revelation, not merely by human decision. President Kimball presented the matter for divine approval even when a majority of apostles were inclined to change—underscoring his desire to have God’s confirmation rather than caving to opinion en.wikipedia.org[2] en.wikipedia.org[2]. In LDS belief, this makes a crucial difference: it was God’s church to direct. The overwhelming joy and spiritual outpouring reported by those in 1978 and by members worldwide is seen by believers as evidence of God’s hand. Even some outside observers, while skeptical of prophetic claims, have noted that the Church structure and culture required a spiritual solution to this issue, not just a policy tweak. In short, yes, public pressure and the moral zeitgeist set the stage, but the Church maintains that only revelation—not rebellion—ended the ban newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3] newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3].

Criticism 3: “Mormon leaders taught racist doctrines before 1978, so how can they be prophets? Why trust a church that promoted racism?”

Fact Check: It is an undeniable fact that some past LDS leaders made racist statements that are disturbing to read now. Quotes from Brigham Young, Joseph Fielding Smith, Mark E. Petersen, and others reflecting theories of Black inferiority or curses are often cited by critics. The LDS Church today agrees that those ideas were wrong. It has explicitly rejected the previous teachings that were used to justify the ban archive.sltrib.com churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. This renunciation is essentially an admission that those leaders were speaking from limited human understanding, not from divine revelation, on this topic. Latter-day Saints reconcile this by understanding that prophets are mortals who (except when moved upon by the Holy Spirit) can err in cultural opinions.

LDS scripture does not teach prophetic infallibility; indeed, prophets have historically made mistakes (e.g., biblical figures like Peter showed bias until corrected—see Galatians 2:11-14). What matters in Mormon belief is that when the Lord does speak, His authorized servants follow that direction. In 1978, the living prophet and apostles demonstrated humility and willingness to set aside all prior teachings once God’s will was revealed. Elder Bruce R. McConkie’s instruction to “forget everything” said before that was contrary to the new revelation encapsulates this stance en.wikipedia.org[2]. That may be unsatisfying to some, but to Church members it shows that the Church can receive new light and adjust, which is a core tenet of a living church led by ongoing revelation. In evaluating the prophetic gift, Latter-day Saints look at the totality of a prophet’s teachings and the fruits thereof. Spencer W. Kimball’s courageous pursuit of the 1978 revelation is seen as a fruit of true prophetic leadership, correcting a past wrong. The Church also believes that God will judge past leaders by the knowledge and context they had—many spoke paternalistically but may not have fully grasped the hurt caused. What’s clear now is that racism of any kind is sinful and contrary to God’s will, and any past statements otherwise were in error. Modern prophets have borne strong witness of this truth newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3] newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3]. In sum, while past leaders said things that we now condemn, LDS belief holds that prophetic authority is still valid—prophets are divinely authorized but not omniscient, and revelation unfolds progressively (“line upon line, precept upon precept”).

Criticism 4: “Why hasn’t the LDS Church issued a formal apology for the priesthood ban?”

Fact Check: This is a question even many faithful Latter-day Saints have pondered. It is true that the Church as an institution has not formally apologized for the ban or the past racism associated with it en.wikipedia.org[2]. Some other religious organizations (e.g., the Catholic Church, Southern Baptist Convention) have issued apologies for past racism or segregation. The LDS Church’s approach has been slightly different: rather than an apology, it has issued powerful acknowledgments and condemnations of the past policy and its premises. The 2013 Race and the Priesthood essay, for example, essentially said the ban was wrong-headed and hurtful, even if it stopped short of the word “sorry.”

Church leaders have expressed regret and sorrow for the pain caused. For instance, in 2018 at the 40th anniversary of the revelation, Elder Dallin H. Oaks (now First Counselor in the First Presidency) reflected on the “hurt” that the restriction caused and urged members to “heed the commandment to love one another” and move forward in unity en.wikipedia.org[2]. He also noted that the reasons for the ban were not fully known and that the Lord “rarely gives reasons” for commandments, implying that sometimes we are simply tested by things we don’t understand en.wikipedia.org[2]. The lack of a formal apology may be due to several factors: (1) a concern that apologizing for a past policy implemented by revered prophets could shake members’ faith in prophetic leadership; (2) a belief that the 1978 revelation and subsequent statements speak for themselves in correcting the injustice; or (3) a desire to focus on the future rather than rehash the past. That said, nothing doctrinal prevents an apology, and some LDS leaders (in personal capacities) have made reconciliatory gestures. For example, President Gordon B. Hinckley, in a meeting with a Black congregation in 2006, personally apologized for any pain caused by past racism blacklatterdaysaints.org patheos.com[4].

Ultimately, whether an official apology comes or not, the Church’s emphasis has been on changing hearts and ensuring such discrimination never recurs. From a believer’s perspective, the sincerest form of apology is in the Church’s actions: vigorously rooting out racism among its membership and leadership, which it continues to strive to do.

In weighing these criticisms, one must remember that the LDS Church today stands firmly for racial equality and unity. The journey from 19th-century attitudes to current teachings has been one of significant transformation—what one historian called “another step in the maturation” of the faitharchive.sltrib.com archive.sltrib.com. It requires Latter-day Saints to reconcile faith in prophetic guidance with the reality of human influence. Many have found resolution in trusting that God, in His own time, set right what needed to be set right, and that the Restored Church is capable of growth and repentance. The objective truth is that the priesthood ban was an error born of prejudice; the faithful LDS perspective is that God allowed it for a time for His own purposes (known or unknown) and then, when the time was right, He corrected it through revelation.

Conclusion

The history of the LDS Church’s priesthood and race policy is a sobering example of how divine principles can be obscured by mortal traditions—and how truth prevails through continuing revelation. For 126 years, Black Latter-day Saints bore a heavy burden with grace and faith, looking forward to the day of inclusion. That day arrived in 1978, which stands as a testament that, in the LDS view, the Lord leads His Church in His own due time. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints today affirms that the worth of souls is great in the sight of God—all souls, without exception. It teaches that God “hath made of one blood all nations” (Acts 17:26) and that no person should be denied any blessing because of color or ethnicity churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

By confronting its past, the Church has learned vital lessons. It has publicly disavowed past folklore and racism churchofjesuschrist.org[1], and in doing so, it offers a message of repentance and hope. The narrative of priesthood and race is now presented openly, not to blame past generations, but to ensure that such errors are not repeated. Members are taught to examine any cultural or personal prejudices and root them out, for one cannot be a true disciple of Christ while harboring racism newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3]. In recent years, the Church has partnered with the NAACP and other groups to further racial harmony, showing its commitment to live the principle that “[God] denieth none that come unto Him” churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

For those struggling with this chapter of LDS history, it is hoped that this comprehensive exploration provides clarity. The objective facts show a church grappling with the paradox of divine gospel and human weakness. The LDS perspective finds resolution in a God who ultimately “will have all men to come unto him” and who requires His followers to overcome prejudice. The Church professes that it is “bound by the Lord”—meaning it moves according to revelation. Sometimes, as in this case, waiting on the Lord’s timing tested patience and compassion. But when that timing was fulfilled, the result was a profound affirmation that God’s love is for everyone—with the Church leadership, membership, and doctrine finally aligned with that eternal truth.

In sum, the priesthood and race issue in Mormonism teaches that while institutions and people may falter, truth and righteousness have the power to triumph over tradition. The LDS Church today wants the world to understand that any notions of racial hierarchy were wrong and are not part of what it stands for. It declares with prophetic clarity that “anyone who is righteous—regardless of race—is favored of [God]” churchofjesuschrist.org[1]. All are invited to partake of every blessing the Lord offers. With this understanding, Latter-day Saints strive to move forward as one family of God, healed by Christ’s love, and united in the knowledge that indeed “black and white, bond and free”—and all shades in between—are alike unto God churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Sources:

Gospel Topics Essay: “Race and the Priesthood,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1] churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

The Salt Lake Tribune, “Mormon church traces black priesthood ban to Brigham Young,” Peggy Fletcher Stack (Dec. 2013) archive.sltrib.com archive.sltrib.com.

Minutes of Utah Territorial Legislature, Jan–Feb 1852 (Brigham Young’s speeches) as cited in Gospel Topics essay churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Lester E. Bush Jr., “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 8:1 (1973), and Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks (1981)—scholarly works establishing the ban’s origin with Brigham Young.

Gregory A. Prince, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (2005)—discusses McKay’s attempts to change the policy churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Edward L. Kimball, “Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood,” BYU Studies 47:2 (2008)—details the events leading to the 1978 revelation en.wikipedia.org[2] en.wikipedia.org[2].

Official Declaration 2 (1978), Doctrine and Covenants—the formal announcement of the revelation ending the ban churchofjesuschrist.org[1].

Bruce R. McConkie, “All Are Alike Unto God,” speech Aug. 1978—instructing members to discard previous racist teachings en.wikipedia.org[2].

Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Need for Greater Kindness,” Conference talk, Apr. 2006—denouncing racial intolerance among Church members newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3] newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org[3].

Dallin H. Oaks, remarks at 40th Anniversary of the Revelation, June 2018—acknowledging pain of pre-1978 policy and urging unity en.wikipedia.org[2].

These sources and the LDS Church’s own statements make it clear that while the Church’s past on racial matters is complicated and regrettable, its present and future are focused on living the truth that God’s priesthood and blessings are for every one of His children. The Church asks its members and the public to judge it by its fruits today—by the lives of Latter-day Saints who strive to love one another without regard to race, truly modeling the belief that we are all brothers and sisters in the family of God.

Footnotes

- https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics-essays/race-and-the-priesthood?lang=eng ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1978_Revelation_on_Priesthood ↩︎

- https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/ldsnewsroom/eng/background-information/president-gordon-b-hinckley-on-racial-intolerance ↩︎

- https://www.patheos.com/latter-day-saint/pastor-to-pastor-margaret-blair-young-09-18-2012?p=2 ↩︎